The client

This steel company is the largest manufacturer of steel long products in Australia. The company has revenues of $3 billion, over 200 operational sites in Australia and New Zealand, more than 30,000 customers and employs approximately 6,900 people.

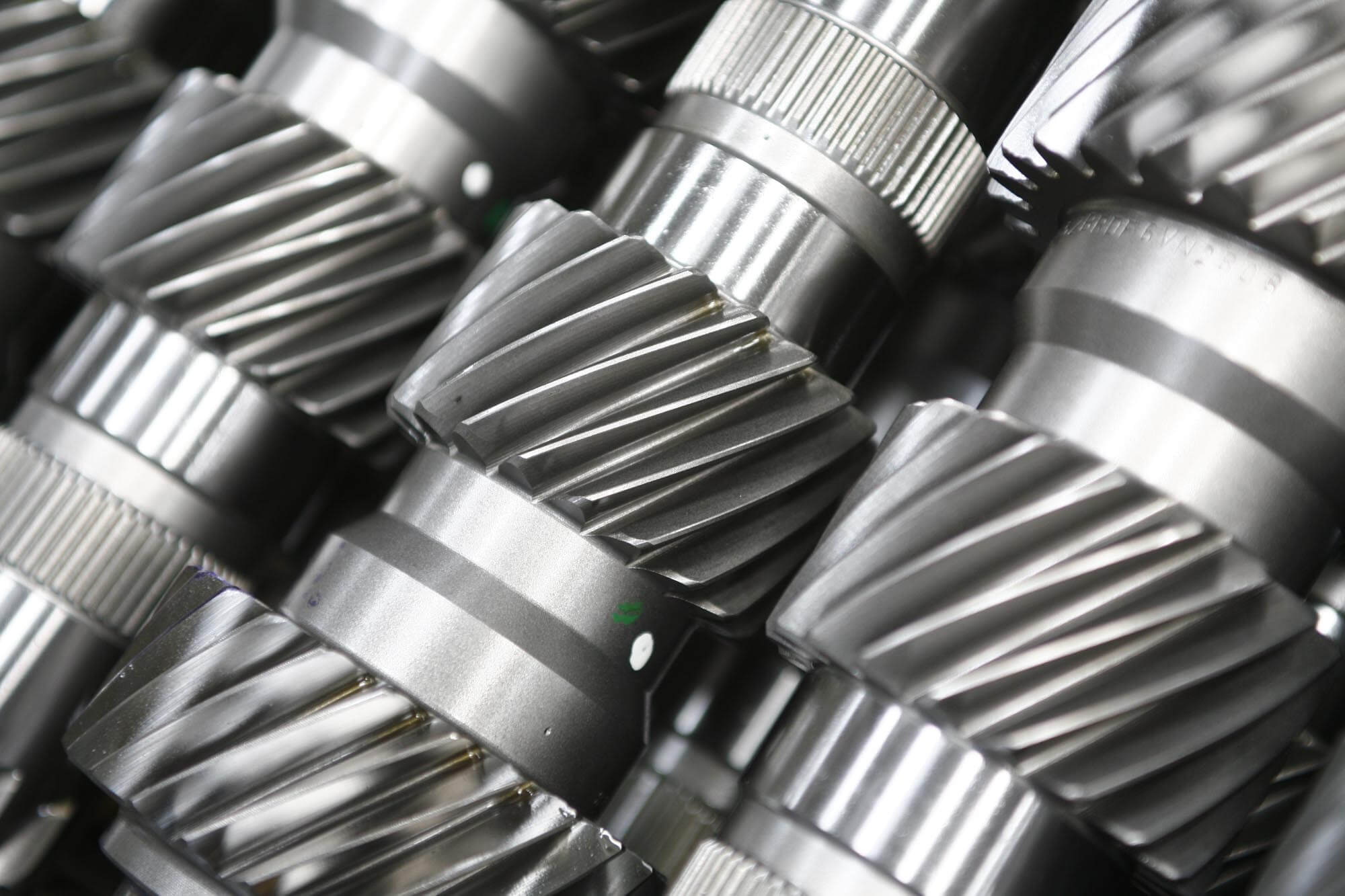

The company’s steelworks in South Australia is the engine room of its Australian operations. It is here that iron ore is converted to molten iron (hot metal) then to raw steel and finally cast into a variety of products.

“Although this is an integrated steelworks, integration was the one component most clearly lacking. There was inconsistent planning, communication and cooperation between sections – and even within sections. This resulted in significant waste of expensive hot metal and often kept management in reactive mode; fighting to overcome problems and keep the plant operational.”

The company’s South Australian steelworks operates 365 days a year. Sixty five per cent of its output is steel slabs that are transferred to the company’s mills in Newcastle. The balance is converted into finished products – usually structural steel sections.

Not my area, not my fault

Like managers in most large organisations, this company’s team had been through a considerable amount of management development training – quality systems, problem solving, root cause analysis etc. But while they understood the training, and could see the benefits, they were not putting it to good use. In part this was because of an attitude of ‘we know better’ and in part because the issues were always deemed to be in someone else’s area.

When problems were identified and fixed this was often done in isolation – creating new problems in, or simply transferring them to, other stages of the production chain. (The two key processes – Basic Oxygen Steel Making (BOS), and Casting – were overseen by separate managers and run by separate shift managers.)

Can’t Stop Now

Steel-making does not offer a lot of room for error. If the process is interrupted or halted the steel in ladles often has to be dumped. The preceding effort and expense, from mining the iron ore onward, is rendered worthless or its value severely depleted. At the steelworks they were dumping around 5000 tonnes of hot metal per month – steel that could have been profitably sold.

The cause was not one of poor planning per se; planning within each section was reasonably good. Planning between them wasn’t. By way of example, the maintenance department would prepare a service schedule only to be told at the last minute that, due to an urgent order, they have to postpone it. The flow-on effect was that equipment would break down and could not – because of the high temperatures – be quickly repaired. Similarly, liquid steel would be poured ready for casting at which point the company’s team would discover that the Casting section was not ready for it. In keeping with the spirit at the steelworks, staff would be creative and resourceful in an attempt to solve the problem. However, there is a limit to how long they can wing it before the steel either has to be dumped or downgraded.

Willing and ready

The steelworks in South Australia is a remote site. The adjacent town has a population of around 22,000, all of whom, directly or indirectly have their livelihood linked to the company. Due to its remoteness, it is a difficult site to recruit to. On the flip side, there are not many other well-paid employment opportunities in the area, so staff loyalty is high. Unsurprisingly, the average length of employment is 23 years and the work and social culture are deeply entrenched.

Despite this, the majority of supervisors and managers were alert to the problems on site and knew that changes had to be made. And soon. The imminent relining of the blast furnace – in itself a major project that experienced a fair share of dramas and publicity – was expected to add a significant capacity to the plant. In order to take advantage of this capacity, the rest of the steel making process had to become more efficient.

Same equipment, same people, different plan

A Continuous Improvement team was formed comprising managers from different departments in Steelmaking, and GPR Dehler consultants.

A series of workshops were held involving 200 of the 300 employees. These generated input from all functions, enabled managers and operators to gain an understanding of the issues their colleagues face, enabled ideal planning and reporting processes to be identified and agreed upon, and ensured that any proposed changes were practical and would be readily-adopted.

Based on these, the CI team developed and installed a new integrated planning and management operating system. This went far beyond daily operations. It linked the quarterly plans set by senior managers, to the weekly plans set by shift managers and process controllers, to the daily plans set by operators.

Roles and responsibilities, aligned to the system’s needs, were revised and clarified – so that everyone knows who is responsible for what tasks. New communication procedures between the sections were established, and service agreements were documented. These were simplified into bullet points covering timing, quantities, measurement and other critical aspects of operations.

In the process of developing the new system, the steelworks team members were actively taught new management skills – ranging from how to run a meeting and achieve the outcomes they need through to developing and producing a fully integrated plan and getting different teams and sections to agree to it.

A taste of things to come

Our client has achieved substantial operational improvements that impact directly on the company’s bottom line profits. It is also positioned for continuous improvement through a management team that now has the skills to design effective process changes and the track record to secure the broad cooperation needed to implement it.

Easy on paper

This project, like many of our engagements, looks straightforward on paper. The reality is far from it. Our skill is not just in identifying problems and designing solutions, but in making those solutions work often in a tough business and cultural environment.

GPR Dehler has an excellent record of implementing change programs in Australia, New Zealand, Asia, Europe, North America and Southern Africa. Everything we do is geared towards achieving results not writing reports. We have the management and planning skills as well as hands-on consultants with experience to overcome obstacles and transform good ideas into effective and successful programs. Significantly, we do this with minimum disruption to our clients’ business operations.